Kaldor’s trade cycle model is a significant contribution to the understanding of business fluctuations in macroeconomics. Developed by Nicholas Kaldor, this model attempts to explain the cyclical nature of economic activity, shedding light on how economies move through different phases—expansion, peak, contraction, and recovery. Unlike other models of economic cycles that focus primarily on exogenous shocks, Kaldor’s model takes into account endogenous factors such as investment and income dynamics that lead to business cycle fluctuations.

In this article, we will explore Kaldor’s contribution to understanding trade cycles, provide numerical illustrations for better comprehension, and examine how the notion of hysteresis further explains the long-term effects of economic downturns.

Kaldor’s Model of Trade Cycles: Understanding the Phases

The Kaldor model explains how economies tend to move in cyclical phases due to the interactions between investment and income. According to Kaldor, fluctuations in economic activity occur as a result of the dynamic relationship between marginal efficiency of capital (investment returns) and changes in income.

The model is fundamentally based on two core assumptions:

- Investment depends positively on income growth—the higher the income growth, the greater the level of investment.

- There is a lagged response between changes in investment and their effect on income.

These two elements create an inherent instability in the economy, as increases in income lead to higher investments, which further boost income, thus creating an expansionary phase. However, as the economy reaches full capacity, diminishing returns set in, and the rate of investment growth starts to slow. This leads to a peak and eventually a contraction phase as investment falls, reducing income and creating a downward spiral. Once excess capacity is eliminated and costs reduced, the economy enters a recovery phase, setting the stage for a new cycle.

A key feature of Kaldor’s model is its ability to illustrate how economic cycles are endogenously generated rather than being purely the result of external shocks. The interplay between investment and income ensures that economies are always in flux, with periods of booms inevitably leading to busts, followed by recoveries. This interplay also helps explain the self-reinforcing nature of economic expansions and contractions, where optimism and increased investment fuel growth, whereas pessimism and declining investments exacerbate downturns.

Visualizing Kaldor’s Trade Cycle Model

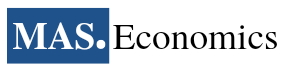

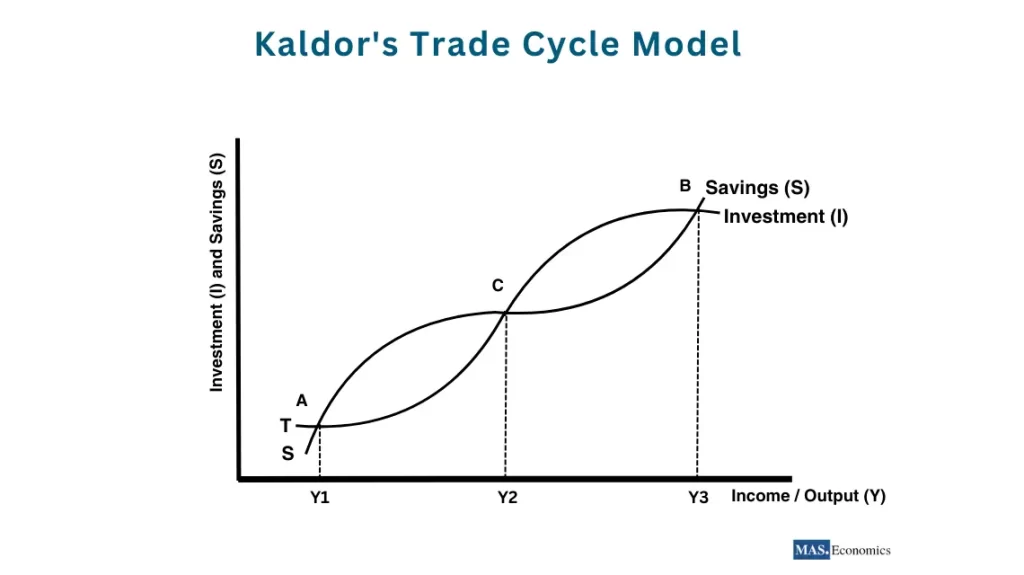

To better understand the dynamics between investment and savings and how they lead to cyclical economic movements, consider the diagram below that illustrates Kaldor’s Trade Cycle Model.

In the diagram, Investment (I) and Savings (S) are depicted as cyclical functions of Income/Output (Y). The key points—A, B, C, and others—help explain different phases of the trade cycle:

- Point A: This point represents the beginning of an economic expansion. At this stage, Investment exceeds Savings, leading to a period of increased economic activity, higher income, and eventually an economic boom.

- Point B: At this point, Savings exceeds Investment as the economy reaches its peak. This marks the beginning of a contraction phase, where the reduced investment slows economic growth.

- Point C: This point represents the recovery phase. Here, investment begins to rise again, eventually surpassing savings, which helps drive the economy back into a period of growth.

This cyclical behavior, illustrated in the diagram, demonstrates how Investment and Savings interact to drive the economy through different phases of the trade cycle. The model provides valuable insights into why economies do not remain static but instead fluctuate between growth and decline.

Numerical Illustration of Kaldor’s Trade Cycle

To better understand Kaldor’s trade cycle model, let’s consider a simplified numerical example. Imagine an economy where investment \(I_t\) depends on current income \(Y_t\) and previous income growth \(\Delta Y_{t-1}\). Let the investment function be given by:

In this equation, \(a\) represents autonomous investment, which is independent of income changes and \(b\) is the marginal propensity to invest, indicating how sensitive investment is to changes in previous income.

Suppose that in period \(t – 1\), income \(Y_{t-1}\) grows by 5%, and the marginal propensity to invest \(b\) is 0.6. If autonomous investment \(a\) is 100, then the investment in period \(t\) would be:

This increase in investment leads to further growth in income in the next period, creating an expansionary effect. However, as income continues to rise, capacity constraints may lead to diminishing returns, eventually causing investment to slow down and triggering a contraction in economic activity.

Hysteresis and Long-Term Effects of Economic Downturns

Another important concept to consider when analyzing trade cycles is hysteresis. Hysteresis refers to the possibility that a temporary economic shock may have permanent effects on the level of output and employment. In the context of Kaldor’s trade cycle, prolonged economic downturns can lead to a loss of productive capacity and skills among the labor force, making it more difficult for the economy to fully recover even after the initial shock has dissipated.

For instance, during a recession, firms cut back on investment, leading to lower income and employment. Workers who lose their jobs may remain unemployed for extended periods, leading to skill erosion and making it harder for them to re-enter the workforce during a recovery. This phenomenon can reduce the potential output of the economy in the long term, causing a permanent reduction in growth prospects.

The concept of hysteresis highlights the importance of timely and effective fiscal policy to counteract downturns and prevent long-term scarring effects. By implementing expansionary fiscal policies—such as increased government spending or targeted tax cuts—governments can help to sustain demand and support employment, thereby reducing the risk of hysteresis. Additionally, policies that support job training and skill development during downturns can further mitigate the negative long-term effects of economic contractions.

Role of Fiscal Policy in Stabilizing Business Fluctuations

Fiscal policy plays a crucial role in managing business cycle fluctuations, especially within the context of Kaldor’s trade cycle model. By influencing aggregate demand, fiscal policy can help to smooth out the cyclical phases of expansion and contraction, minimizing the volatility of economic activity.

For example, during an economic downturn, counter-cyclical fiscal policy—such as increased infrastructure spending—can provide an immediate boost to aggregate demand, shifting the economy from contraction to recovery. This aligns with Kaldor’s view that active government intervention is necessary to stabilize economic cycles and mitigate the adverse effects of downturns. By boosting infrastructure projects, governments not only create jobs but also lay the foundation for future growth by enhancing productivity.

Conversely, during periods of economic boom, contractionary fiscal policies—such as reducing government expenditure or increasing taxes—can be employed to prevent the economy from overheating and to maintain sustainable growth levels. The timing and magnitude of these policy interventions are critical to ensuring that they effectively counteract the cyclical forces at play.

In addition to direct fiscal measures, automatic stabilizers—such as progressive taxation and unemployment benefits—also play an essential role in moderating the fluctuations of economic cycles. Progressive taxation reduces disposable income during booms, thereby limiting excessive consumption, while unemployment benefits provide support to those who lose their jobs during downturns, helping to maintain aggregate demand.

Real-World Applications

The Kaldor trade cycle model can be applied to understand historical economic fluctuations and the policy responses used to manage them. For instance, the Great Recession of 2008-2009 can be analyzed through the lens of Kaldor’s model, where a decline in investment led to a sharp contraction in income, creating a downward economic spiral. The subsequent fiscal stimulus packages implemented by governments worldwide—such as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) in the United States—served to stabilize aggregate demand and support recovery, aligning with Kaldor’s emphasis on active fiscal intervention.

Another example is the economic cycle experienced by Japan during the 1990s, often referred to as the “Lost Decade”. After the asset bubble burst, investment in Japan plummeted, leading to a prolonged period of economic stagnation. Despite multiple fiscal stimulus packages, the economy struggled to recover due to the severity of the contraction and the presence of hysteresis effects, which left lasting scars on Japan’s economic potential.

Conclusion

Kaldor’s trade cycle model provides a valuable framework for understanding the endogenous nature of economic fluctuations and the role of investment dynamics in driving business cycles. By emphasizing the interplay between income and investment, Kaldor’s model highlights the importance of fiscal policy in stabilizing economic activity and preventing prolonged downturns that can lead to hysteresis and long-term economic damage.

Incorporating real-world examples helps illustrate the practical relevance of Kaldor’s model and the need for active policy intervention to manage business cycles. Whether dealing with the aftermath of a financial crisis or striving to sustain economic growth.

FAQs:

What is Kaldor’s trade cycle model?

Kaldor’s trade cycle model explains the cyclical nature of economic activity through endogenous factors like the interaction between income and investment. According to Kaldor, investment depends on income growth, and this dynamic relationship creates self-reinforcing cycles of economic expansion, contraction, and recovery. As income rises, investment increases, boosting further income growth. However, diminishing returns eventually slow investment, triggering economic downturns.

How does the interaction between investment and income create economic cycles?

In Kaldor’s model, when income rises, investment increases because businesses expect higher returns. This leads to economic expansion. However, once the economy reaches full capacity, the returns on new investments decline, causing businesses to reduce investment. This slowdown reduces income, triggering a contraction phase. Eventually, the economy stabilizes, setting the stage for a recovery and the beginning of a new cycle.

What is hysteresis, and how does it affect long-term economic performance?

Hysteresis refers to the long-term effects of temporary economic shocks. Prolonged downturns can reduce an economy’s productive capacity by causing skill erosion and long-term unemployment, making recovery more difficult. Workers who remain unemployed for extended periods lose skills, reducing their employability. As a result, even after the economy recovers, its potential output may remain lower than before the downturn.

Why is fiscal policy essential in Kaldor’s trade cycle model?

Fiscal policy plays a crucial role in stabilizing economic fluctuations by influencing aggregate demand. During downturns, governments can use expansionary fiscal policies, such as increasing infrastructure spending or cutting taxes, to boost demand and support recovery. This aligns with Kaldor’s view that active intervention can prevent severe downturns and mitigate the risk of hysteresis. Conversely, during economic booms, contractionary fiscal policies can prevent overheating by reducing government spending or raising taxes.

How do automatic stabilizers complement fiscal policy during economic cycles?

Automatic stabilizers, such as progressive taxation and unemployment benefits, play a vital role in moderating economic fluctuations. During booms, progressive taxation reduces disposable income, curbing excessive consumption. In downturns, unemployment benefits provide income support to those who lose their jobs, helping maintain aggregate demand. These automatic mechanisms ensure that fiscal policy responds to economic conditions without requiring constant government intervention.

How does Kaldor’s model differ from other business cycle theories?

Kaldor’s model focuses on endogenous factors like investment and income dynamics rather than relying on external shocks to explain economic cycles. It emphasizes the self-reinforcing nature of expansions and contractions, where optimism drives investment during booms, and pessimism reduces investment during downturns. This makes Kaldor’s model particularly relevant for understanding how economies naturally fluctuate over time.

What are the policy implications of Kaldor’s trade cycle model?

Kaldor’s model underscores the need for proactive fiscal policies to manage economic cycles. Governments should implement expansionary policies during downturns to prevent prolonged contractions and limit the impact of hysteresis. During booms, contractionary policies can help maintain sustainable growth and prevent inflationary pressures. The model also highlights the importance of balancing fiscal intervention with long-term strategies like job training programs to reduce the long-term effects of economic downturns.

Thanks for reading! Share this with friends and spread the knowledge if you found it helpful.

Happy learning with MASEconomics