Welcome to MASEconomics, your guide to the world of economics. In this blog article, we’ll learn about the costs of production, the necessary expenses that companies incur to produce goods and services. These costs are the fundamental building blocks of economics, profoundly influencing how products are created, priced, and brought to market. Understanding these costs is crucial for businesses, as they are essential for profit maximization and strategic decision-making.

Short-Run and Long-Run Cost Dynamics

When assessing a firm’s costs, we must consider two distinct time frames: the short and long run.

- Short-run: Firms can adjust labor and raw material usage during this period, but capital and land resources remain fixed and unalterable.

- Long-run: In the long run, firms gain the flexibility to vary all resources they use in production, including labor, capital, and land resources. This flexibility opens up opportunities for growth and efficiency.

To illustrate:

Imagine a small bakery in the short run. It can hire or fire bakers (labor) and buy or sell ovens (capital). However, it can’t change the size of its kitchen (land resources). In the long run, if the bakery wants to expand its operations, it can lease a more oversized kitchen, buy more ovens, and hire more bakers.

Types of Costs

Let’s begin by distinguishing between two fundamental categories of costs: fixed costs (FC) and variable costs (VC).

In the short run, firms face both variable and fixed costs:

Fixed Costs (FC)

Fixed costs include administrative salaries, rent, insurance, and equipment depreciation. These costs remain constant, irrespective of production levels.

Variable Costs (VC)

In contrast, variable costs encompass expenditures like raw materials, labor wages, and energy consumption, which directly relate to the quantity of output.

Together, these costs form the financial foundation upon which businesses base their critical decisions.

In the long run, all costs become variable, as firms can adapt their resource allocation according to changing production requirements.

The Law of Diminishing Returns

As more of a variable resource, typically labor, is added to fixed resources like capital and land towards production, the marginal product of the variable resource will increase until a certain point, beyond which marginal product declines.

Consider a factory that uses labor and machinery to produce cars. Initially, hiring more workers boosts production, but at a certain point, adding more laborers to the same machinery becomes counterproductive, leading to a decline in the marginal product of labor.

The table below presents some primary costs a firm faces and indicates whether they are fixed or variable costs:

| Cost Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Fixed Costs (FC) | – Rent (payment for land) – Interest (payment for capital) – Depreciation – Insurance premiums – Property taxes – Administrative costs |

| Variable Costs (VC) | – Wages (payment for labor) – Raw materials – Energy costs – Transportation costs – Marketing costs – Packaging costs |

|

|

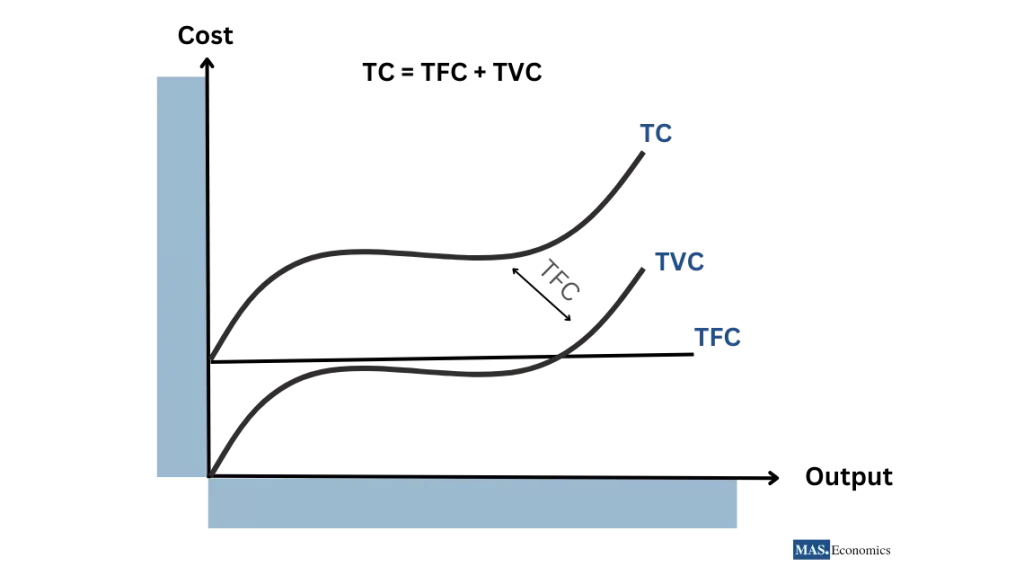

Total Costs in the Short-run

To delve deeper into microeconomics, it’s essential to grasp the concept of total costs (TC). Mathematically, TC is represented as TC = FC + VC, encompassing a firm’s financial outlay for a specific production level. Total costs serve as a guiding metric for businesses, aiding in assessing profitability and making informed resource allocation decisions.

Total Fixed Costs (TFC)

These are the costs that do not vary with changes in short-run output. Examples include rent on factory space and interest on capital.

Total Variable Costs (TVC)

These are the costs that change with the level of output in the short run. They include payments for raw materials, fuel, power, transportation services, and wages for workers.

TC = TFC + TVC at each level of output.

Consider a widget manufacturing company. Its total fixed costs include rent for its factory and the interest paid on loans for machinery. Variable costs include expenses like raw materials, electricity for the machinery, and wages for production workers.

Graph 1 visually elucidates the interplay between total cost, fixed cost (FC), and variable cost (VC). The total cost line represents the summation of fixed and variable costs across various production levels. While the fixed cost line remains steady, the variable cost line fluctuates with production volume. This graphical representation facilitates a deeper understanding of the distinct contributions of these cost components to a company’s overall financial landscape.

Firms make decisions about their output levels based not on total costs but on per-unit and marginal costs.

The Significance of Per-unit Costs (Average Costs) in the Short-run

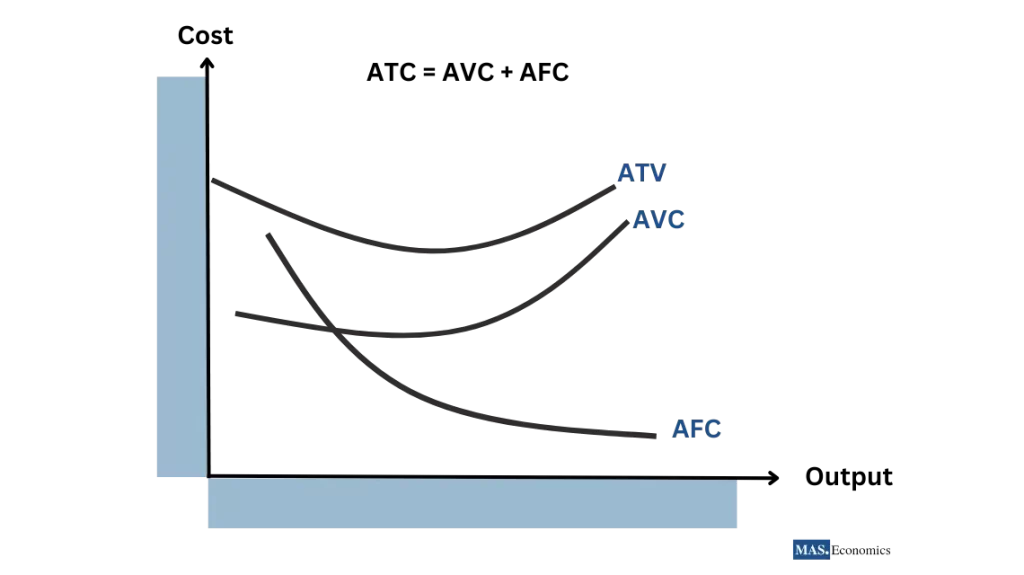

Now, let’s transition to a more detailed examination of average costs, which provide invaluable insights into cost efficiency and operational viability. Average costs consist of three vital dimensions:

- Average Fixed Cost (AFC): AFC = TFC / Q. Calculated by dividing total fixed costs by the quantity of output, AFC plays a central role in our discussion. As production scales up, AFC proportionally declines, influencing businesses’ decisions regarding expansions or new ventures.

- Average Variable Cost (AVC): AVC = TVC / Q. Determined by dividing total variable costs by the quantity of output, AVC typically follows a U-shaped curve. It initially decreases due to economies of scale but ultimately ascends due to diminishing returns. AVC helps identify the optimal production level that minimizes costs per unit.

- Average Total Cost (ATC): ATC = TC / Q. ATC, the sum of AFC and AVC, traces a U-shaped curve analogous to AVC. This metric proves critical for pricing decisions and determining the production level that maximizes efficiency while minimizing waste.

Graph 2 visually depicts the relationship between average fixed costs (AFC), average variable costs (AVC), and average total costs (ATC). As production levels shift, AFC generally declines due to economies of scale, while AVC initially decreases before ascending due to diminishing returns. The ATC curve, the summation of AFC and AVC, imparts insights into the cost per unit of output, aiding businesses in pricing and production decisions.

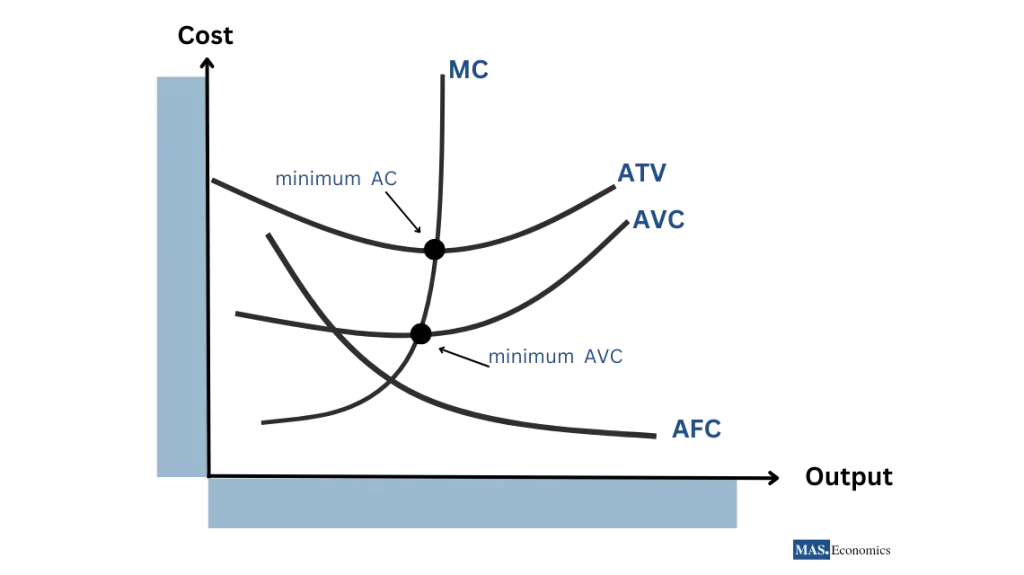

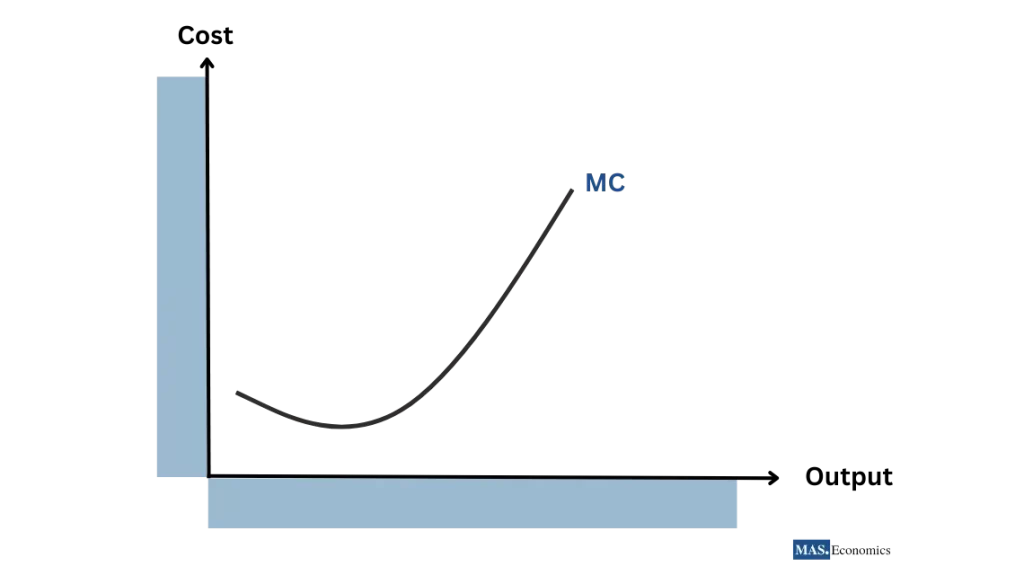

The Role of Marginal Cost (MC)

Let’s focus on marginal cost (MC) in short-term production decisions. MC signifies the additional cost incurred when producing one other unit and is calculated as the change in total cost divided by the change in quantity. This metric is a guiding star for firms in optimizing production levels, with profit maximization occurring when marginal cost aligns with marginal revenue.

Graph 3, on the right side, represents the Marginal Cost (MC) Curve, visualizing how the incremental cost of producing one additional unit evolves with varying production levels. Firms aspire to maximize profits by aligning MC with marginal revenue, a crucial strategy highlighted by this curve. The significance of MC extends beyond profit maximization, finding relevance in domains such as public goods provision and environmental regulation.

Graph 4 illustrates how the MC curve intersects with the ATC curve and AVC curve at their minimum points, showing that the cost of producing one more unit of output equals the average cost of producing all output units, indicating only variable charges are incurred.

Costs of Production in the Long run

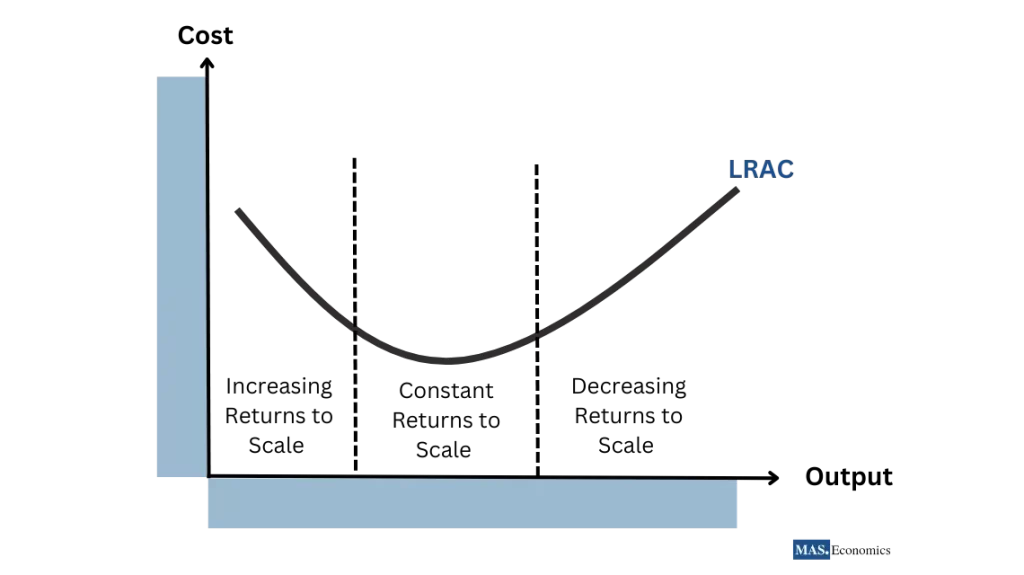

In the long run, firms can open new plants, add capital to existing plants, or close plants and remove capital as needed. Since capital and land are variable in the long run, the law of diminishing returns no longer applies.

Three Ranges of a Firm’s Long-run Average Total Cost (LRAC) Curve

Increasing Returns to Scale (Economies of scale)

Firms receive increasing amounts of output per additional unit of inputs (land, labor, and capital). Average costs decrease as output increases due to better specialization, division of labor, bulk buying, lower interest on loans, lower per-unit transport costs, larger and more efficient machines, and other factors.

Constant Returns to Scale

Firms receive the same amount of output per additional unit of input. Average costs do not change as output increases.

Decreasing Returns to Scale (Diseconomies of Scale)

Firms experience diminishing returns as they become “too big for their good.” The output per unit of input decreases as more inputs are added. Average costs increase as output increases due to control and communications problems, inefficiencies in coordinating production across broad geographic areas, and other factors.

The U-shaped LRAC curve in Graph 5 shows how the minimum average cost of producing a unit of output varies with the output level. It’s due to economies of scale at low levels and diseconomies at high levels. As output increases, fixed costs spread, and average cost reduces, the firm becomes inefficient at very high levels.

Sunk Costs and Rational Decision-Making

A sunk cost is a cost that has already been paid and cannot be recovered. This cost is typical in business and may include research and development, marketing, and advertising fees. When it comes to decision-making, rational choices are based on logical reasoning and information that is available at the time. In such instances, it is essential to disregard sunk costs since these expenses are no longer relevant to future outcomes and should not factor into future decisions.

For example, suppose a pharmaceutical company has invested considerable money in researching and developing a particular drug. In that case, the money spent on this project is considered a sunk cost and should be ignored when deciding whether to keep developing the drug. Instead, the company should focus on the expected costs and benefits of continuing the project. If the company concludes that the drug is unlikely to gain regulatory approval and generate profits, it is best to discontinue the project.

Revenues

While costs are crucial, a firm must also consider its revenues. Revenues are the income the firm earns from the sale of its goods. They include:

- Total Revenue (TR): TR = Price of the good × Quantity sold.

- Average Revenue (AR): AR is the firm’s total revenue divided by the quantity sold or the price of the good.

- Marginal Revenue (MR): MR is the change in total revenue resulting from an increase in the output of one unit.

The Profit-Maximization Rule

To maximize total economic profits, a firm should produce at the output level at which its marginal revenue equals its marginal cost. For perfect competitors, this means producing where marginal cost equals price (MC=P), while for imperfect competitors, marginal cost equals marginal revenue (MC=MR).

The rationale for the MC=MR rule is that if a firm produces where MR>MC, its total profits will rise with increased output, and if it produces where MC>MR, it should reduce its output because additional costs exceed additional revenue. Maximum total profits occur when MC=MR.

Normal Profit and Economic Profit

To maintain long-term success, a company must generate a normal profit. This refers to the profit a company would earn if it operated in a perfectly competitive market.

Economic profit, on the other hand, is when a company makes a profit that exceeds its normal profit. This occurs when a company can charge a price higher than its average production cost.

Industries that offer economic profits tend to attract more firms, providing more significant opportunities to earn profits than other sectors. However, this influx of firms can ultimately lead to increased competition and lower prices, causing economic profits to disappear.

A table has highlighted the key differences between normal profit and economic profit.

| Feature | Normal Profit | Economic Profit |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | The minimum profit that a firm needs to make in order to stay in business in the long run. | The profit that a firm makes above and beyond normal profit. |

| How it is calculated | Total revenue – Total cost | Total revenue – Total cost – Normal profit |

| Occurs in | Perfectly competitive markets | Imperfectly competitive markets |

| Attracts firms | No | Yes |

|

||

Conclusion

Microeconomic costs are pivotal in shaping the landscape of production, pricing, and market behavior for firms. Businesses can make informed decisions that enhance profitability and efficiency by comprehending the different types of costs of production, the interplay between short-run and long-run dynamics, economies of scale, and rational decision-making principles.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this series, spread the knowledge by sharing it with friends and on social media.

Happy learning with MASEconomics!